By Jon Eakes

Both the HRV (Heat Recovery Ventilator) and the ERV (Energy Recovery Ventilator) were developed together in the early 1980s with the promise that the HRV would dehumidify the tightly sealed house. The ERV promised to do the same job while returning 50 per cent of the moisture back to where it came from, thus not drying out a house too much.

Unfortunately, because ERVs actually retained moisture in their exchange cores, they quickly self-destructed with Canada’s freezing temperatures. ERVs literally disappeared from Canada, but became the ventilation mainstay in the hot humid air conditioning climate of Florida. They worked just the opposite down there, keeping outdoor moisture outdoors, thus keeping humidity levels in the air-conditioned house lower, easier to cool, and more comfortable. And they never froze.

|

|---|

Many ERVs Won’t Work in Canada

Although today there are more than 40 companies making ERVs, you must be very careful to check the Home Ventilating Institute (HVI) listings to identify the few models that are rated to last for 10 years at temperatures down to -25C. For several years Venmar had the only unit capable of doing that, although now there are a few more on the market.

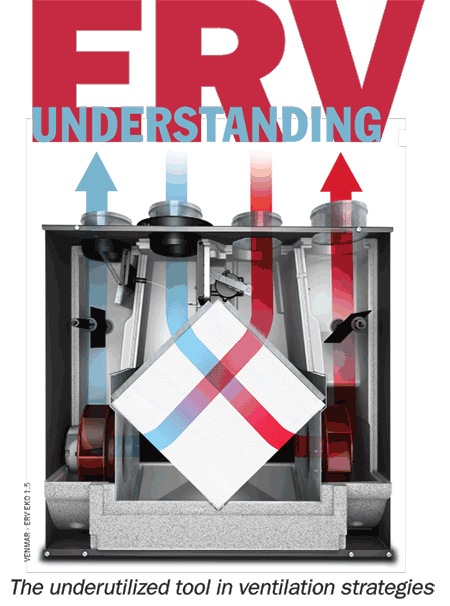

Understanding the Technology

During the Canadian winter an HRV recuperates heat from the outgoing stale air and transfers it to the incoming fresh air, bringing their two temperatures close to the same levels, even though the outgoing air is moist and the incoming air is dry. An ERV does some of the same temperature transfer, but also brings over warm moisture into the fresh air stream.

Leaving more humidity in the house is only part of the story. There is energy stored in that moisture. Very little energy is required to bring this moisture up to room temperature compared to cold vapour coming off a humidifier that just soaks up energy from the space heating system. An ERV recuperates a great deal of “embodied energy” or what is called enthalpy or latent heat, and that is where a good part of its energy recovery comes from. Wet or dry air at the same temperature is much like a cast iron fry pan and a sheet of aluminum foil, both at the same temperature. The massive fry pan has enough energy stored in it to cook your skin; the aluminum foil will be cooled instantly when you touch it because there is little mass to store energy.

|

|---|

Cross flow HRV core |

|

Cross flow ERV core |

How Much Ventilation Should We Have?

For a long time it has been assumed that CO2, generated by human breathing, was a good indicator of indoor pollutants and was used to establish our norms for ventilation rates. But sometimes those official ventilation rates caused problems of their own—from drying out the house to introducing pollution from outside the house that was worse than what was initially inside—and the occupants simply turned the units off. With time, experience and better sealed houses, we have discovered that the ideal ventilation for any given house was far more variable than previously thought.

Some even question our established ventilation calculation formulas. A recent study published by BuildGreenAdvisor.com, Ventilation Rates and Human Health, asked the question: “Have researchers found any connection between residential ventilation rates and occupant health?” The answer was there were not very many studies on the subject and some of them said there was no relationship between the two. Joseph Lstiburek, with his typical frankness, put forward that with a lack of scientific basis for ventilation rates we would be far better off starting by controlling pollution sources. Many cases were also cited where outdoor air was worse than indoor air and any ventilation only polluted the house. I only mention those thoughtful reflections to point out how much each house needs to be studied on its own.

No builder can provide a specific ventilation rate to a house; he can only provide a planned ventilation potential and then, if it works well for that house, the occupants may actually use it.

A healthy air quality strategy is far more than just choosing the model of air exchanger. It is minimizing the need for ventilation by reducing pollution sources, providing point of pollution extraction, maximizing air circulation throughout the house and then taking into account the building’s outdoor environment and the lifestyles of the occupants. Using automated control systems, some measuring outdoor temperatures, others measuring pollution levels, but all offering easily variable ventilation speeds, help these machines to adapt to daily reality and user demands.

Now that cold weather technology has been proven for the ERV, you really do have one more tool to design ventilation strategies that specifically suit your individual customer. Just make sure that you install an ERV that is HVI certified for 10 years down to -25C and not a Florida import.